Beginners Guide to Periodization

Endurance sports, for most people, are pretty daunting even just to consider. For those of us who have chosen to pursue a goal in endurance sports, we’re past the point of consideration. We’re in the planning/execution stage. We have to figure out the best way to prepare ourselves for the challenge that could, in some cases, last longer than 24 hours. Everyone knows we need to consider our training, nutrition, recovery, family and work schedules, etc. Most people would consider the training to be the most important part of making sure you’re ready to go on race day (I believe training and nutrition are equally as important). A good way to build a training plan to reach your goal is through the use of a technique known as periodization. Periodization can be explained as simply as a planning technique used to prevent an athlete from overtraining through structure and specificity.

“Periodization can be explained as simply as a planning technique used to prevent an athlete from overtraining through structure and specificity.”

There are two types of periodization: traditional and reverse. In both traditional and reverse periodized plans, the athlete progresses through various stages of varying volumes and intensities before competition. The traditionally periodized plan will start at the bottom of the pyramid (below) and work up toward the top. Whereas, a reverse plan will start at the top and work toward the bottom. I use and the rest of this guide will be based on a traditional periodization approach.

“I use and the rest of this guide will be based on a traditional periodization approach.”

Periodization is comprised of a macrocycle and many mesocycles and microcycles. A macrocycle contains both mesocycles and microcycles and is usually described as the entire training program. Mesocycles can vary in length but most commonly contain a period of three microcycles, where there are two loading microcycles and one unloading microcycle. Microcycles are generally equivalent to a week and are the most fundamental part of a well-designed training program.

“In both traditional and reverse periodized plans, the athlete progresses through various stages of varying volumes and intensities before competition.”

If you’re lost at this point, you’re in good company. Learning how to create and develop a good training plan is an art and takes time to fully understand. Basically, when you are creating a program, you start with a macrocycle and then develop your meso and microcycles based on the dates of your events. Once you’ve done that, you can start the actual planning of your sessions. To do this I use the six steps listed below.

PhasesStructure

Variables

Frequency

Total Sessions

Objectives

Phases

I like to work with three different phases: preparation, competition, and transition. The preparation phase consists of general and specific subphases. The general phrase is usually where I have my athletes build their “base”. This is where they work on building their volume while keeping the overall intensity relatively low. The purpose is to build their muscles and try to get their bodies ready for the specific prep phase. For specific prep, the goal is to start working on the distances and intensities that the athlete will face during competition. The volume continues to build while intensity increases. The preparation phase can vary in mesocycle length based on the length of time before the athlete's competition. Generally, more training time is better than less, but every athlete’s needs/goals are different.

Structure

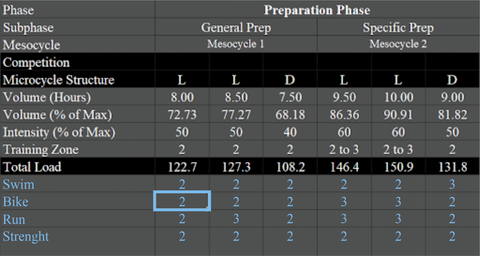

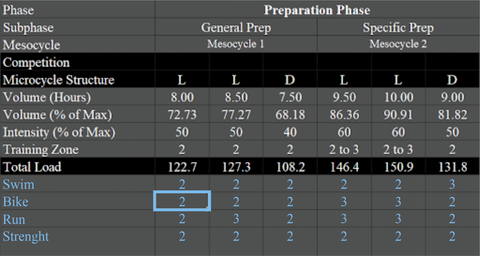

After you determine the lengths of your general and specific prep subphases, you can start working on the structure of both subphases by manipulating the mesocycle (sequence of weeks) length and microcycle (individual week) structure. Two on and one-off has always worked for me and my athletes, however depending on the time until the competition, I have planned a three on and one-off mesocycle before. That said, the length of each mesocycle is up to the designer. The importance of this step really lies in the structure of the microcycles. You have to be mindful of the possibility of overtraining while also trying to build volume and or intensity. For this reason, it is common to overload the body for a period of two weeks and allow the body to actively recover during the third week of the mesocycle to allow for training adaptations to take place.

*Where L and D stand for Loading and Unloading, respectively.

Variables

Step three. Probably the most intimidating step of the six. There are four variables possible variables that you can use when planning, however, it is often sufficient to use only two. The variables are volume (hours), volume (% of max), intensity (% of max), and training zone (intensity). The two most important being volume (hours) and training zone. In the photo below, you can see the steady increase in volume through the general and specific prep subphases while the training intensity remains relatively low. This is what is referred to as “building a base” which is the main purpose of the preparation phase. In general, it is recommended that increases in volume from microcycle to microcycle should stick to the 10% rule. That is, there should only be a 10% increase in volume between microcycles. This is suggested to help prevent overtraining which could lead to injuries or illness. Of course, every athlete is different, so the decision is the responsibility of the designer. The volume (% of max) and intensity (% of max) variables are simply functions of the max volume and intensity throughout the macrocycle. You don’t need these. I only include them so my athletes know what they are getting into and have an idea of how straining each microcycle might be.

Frequency

Now having made it through the variables, you’re ready to determine the frequency of each training session for each sport for each microcycle. This is usually dictated by the volume (hours) that you have predetermined for each microcycle. I tend to schedule my longer workouts on the weekends (end of microcycle) so I start with those sessions and then work my way backward through the week with whatever volume remains. Of course, the session frequency increases as the volume increases throughout the macrocycle leading to competition.

Total Sessions

Step five. We’re almost done. Planning is a huge part of the training. But believe me, trying to train for an event or goal without a training plan is crazy. I’ve tried. I tried planning week to week too. That didn’t go well either. You don’t need to plan your whole year at one time but planning a month or two (at least) at a time will significantly reduce the stress of planning your training and ensure that you get your workouts done. The total session hours step could probably come before frequency in the periodization process, but I feel that it works out to be easier doing it this way. Basically, you are deciding how to split your total volume (hours) to fit the frequency totals that you determined in step four. See? Works, huh? I think so. I also start with the workouts at the end of each microcycle and work backward through the week to determine the total session values. Of course, you have to keep your unloading/training races/competitions in mind when determining the total session values, but your volume (hours) should reflect those events so that shouldn’t be too much of a problem. Time for the last step.

Objectives

Here we are. Just about ready to wrap up a well-designed training plan. The good news is, you’ve pretty much already determined your objectives by determining how long you will spend in each training phase and subphase. Let’s start with testing. I like to test about every three weeks. I believe that a decent amount of progress can be made and reflected in that time. Of course, by testing, I mean lactate threshold testing which I covered in a separate article that you can read here. The remaining objectives can be grouped together in the following ways. Aerobic Endurance, Strength, and Technique. Speed, Power, and Tactics. Active Recovery. You can think of the three groups as the preparation group, the competition group, and the transition group respectively. Thinking of them in this way makes the planning a little simpler. During the preparation phase, you should be focusing on Aerobic Endurance, Strength, and Technique. During the competition phase Speed, Power, and Tactics. During the transition phase Active Recovery.

That’s it. Not too complicated, right? I always think that planning will be easy, but it never actually is as easy as I thought. I love it though. Maybe not so much while I’m planning, but later on when I can see the results in training and testing. Either way, if you want to be your own coach, having a basic knowledge of periodization is essential. You’ll be able to reach your goals while keeping yourself healthy and strong. Good luck with the upcoming season and working toward your goal.

“Either way, if you want to be your own coach, having a basic knowledge of periodization is essential.”

Figure 3.1. Reuter, B. (2012). Developing endurance.

Endurance sports, for most people, are pretty daunting even just to consider. For those of us who have chosen to pursue a goal in endurance sports, we’re past the point of consideration. We’re in the planning/execution stage. We have to figure out the best way to prepare ourselves for the challenge that could, in some cases, last longer than 24 hours. Everyone knows we need to consider our training, nutrition, recovery, family and work schedules, etc. Most people would consider the training to be the most important part of making sure you’re ready to go on race day (I believe training and nutrition are equally as important). A good way to build a training plan to reach your goal is through the use of a technique known as periodization. Periodization can be explained as simply as a planning technique used to prevent an athlete from overtraining through structure and specificity.

“Periodization can be explained as simply as a planning technique used to prevent an athlete from overtraining through structure and specificity.”

There are two types of periodization: traditional and reverse. In both traditional and reverse periodized plans, the athlete progresses through various stages of varying volumes and intensities before competition. The traditionally periodized plan will start at the bottom of the pyramid (below) and work up toward the top. Whereas, a reverse plan will start at the top and work toward the bottom. I use and the rest of this guide will be based on a traditional periodization approach.

“I use and the rest of this guide will be based on a traditional periodization approach.”

Periodization is comprised of a macrocycle and many mesocycles and microcycles. A macrocycle contains both mesocycles and microcycles and is usually described as the entire training program. Mesocycles can vary in length but most commonly contain a period of three microcycles, where there are two loading microcycles and one unloading microcycle. Microcycles are generally equivalent to a week and are the most fundamental part of a well-designed training program.

“In both traditional and reverse periodized plans, the athlete progresses through various stages of varying volumes and intensities before competition.”

If you’re lost at this point, you’re in good company. Learning how to create and develop a good training plan is an art and takes time to fully understand. Basically, when you are creating a program, you start with a macrocycle and then develop your meso and microcycles based on the dates of your events. Once you’ve done that, you can start the actual planning of your sessions. To do this I use the six steps listed below.

PhasesStructure

Variables

Frequency

Total Sessions

Objectives

Phases

I like to work with three different phases: preparation, competition, and transition. The preparation phase consists of general and specific subphases. The general phrase is usually where I have my athletes build their “base”. This is where they work on building their volume while keeping the overall intensity relatively low. The purpose is to build their muscles and try to get their bodies ready for the specific prep phase. For specific prep, the goal is to start working on the distances and intensities that the athlete will face during competition. The volume continues to build while intensity increases. The preparation phase can vary in mesocycle length based on the length of time before the athlete's competition. Generally, more training time is better than less, but every athlete’s needs/goals are different.

Structure

After you determine the lengths of your general and specific prep subphases, you can start working on the structure of both subphases by manipulating the mesocycle (sequence of weeks) length and microcycle (individual week) structure. Two on and one-off has always worked for me and my athletes, however depending on the time until the competition, I have planned a three on and one-off mesocycle before. That said, the length of each mesocycle is up to the designer. The importance of this step really lies in the structure of the microcycles. You have to be mindful of the possibility of overtraining while also trying to build volume and or intensity. For this reason, it is common to overload the body for a period of two weeks and allow the body to actively recover during the third week of the mesocycle to allow for training adaptations to take place.

*Where L and D stand for Loading and Unloading, respectively.

Variables

Step three. Probably the most intimidating step of the six. There are four variables possible variables that you can use when planning, however, it is often sufficient to use only two. The variables are volume (hours), volume (% of max), intensity (% of max), and training zone (intensity). The two most important being volume (hours) and training zone. In the photo below, you can see the steady increase in volume through the general and specific prep subphases while the training intensity remains relatively low. This is what is referred to as “building a base” which is the main purpose of the preparation phase. In general, it is recommended that increases in volume from microcycle to microcycle should stick to the 10% rule. That is, there should only be a 10% increase in volume between microcycles. This is suggested to help prevent overtraining which could lead to injuries or illness. Of course, every athlete is different, so the decision is the responsibility of the designer. The volume (% of max) and intensity (% of max) variables are simply functions of the max volume and intensity throughout the macrocycle. You don’t need these. I only include them so my athletes know what they are getting into and have an idea of how straining each microcycle might be.

Frequency

Now having made it through the variables, you’re ready to determine the frequency of each training session for each sport for each microcycle. This is usually dictated by the volume (hours) that you have predetermined for each microcycle. I tend to schedule my longer workouts on the weekends (end of microcycle) so I start with those sessions and then work my way backward through the week with whatever volume remains. Of course, the session frequency increases as the volume increases throughout the macrocycle leading to competition.

Total Sessions

Step five. We’re almost done. Planning is a huge part of the training. But believe me, trying to train for an event or goal without a training plan is crazy. I’ve tried. I tried planning week to week too. That didn’t go well either. You don’t need to plan your whole year at one time but planning a month or two (at least) at a time will significantly reduce the stress of planning your training and ensure that you get your workouts done. The total session hours step could probably come before frequency in the periodization process, but I feel that it works out to be easier doing it this way. Basically, you are deciding how to split your total volume (hours) to fit the frequency totals that you determined in step four. See? Works, huh? I think so. I also start with the workouts at the end of each microcycle and work backward through the week to determine the total session values. Of course, you have to keep your unloading/training races/competitions in mind when determining the total session values, but your volume (hours) should reflect those events so that shouldn’t be too much of a problem. Time for the last step.

Objectives

Here we are. Just about ready to wrap up a well-designed training plan. The good news is, you’ve pretty much already determined your objectives by determining how long you will spend in each training phase and subphase. Let’s start with testing. I like to test about every three weeks. I believe that a decent amount of progress can be made and reflected in that time. Of course, by testing, I mean lactate threshold testing which I covered in a separate article that you can read here. The remaining objectives can be grouped together in the following ways. Aerobic Endurance, Strength, and Technique. Speed, Power, and Tactics. Active Recovery. You can think of the three groups as the preparation group, the competition group, and the transition group respectively. Thinking of them in this way makes the planning a little simpler. During the preparation phase, you should be focusing on Aerobic Endurance, Strength, and Technique. During the competition phase Speed, Power, and Tactics. During the transition phase Active Recovery.

That’s it. Not too complicated, right? I always think that planning will be easy, but it never actually is as easy as I thought. I love it though. Maybe not so much while I’m planning, but later on when I can see the results in training and testing. Either way, if you want to be your own coach, having a basic knowledge of periodization is essential. You’ll be able to reach your goals while keeping yourself healthy and strong. Good luck with the upcoming season and working toward your goal.

“Either way, if you want to be your own coach, having a basic knowledge of periodization is essential.”

Figure 3.1. Reuter, B. (2012). Developing endurance.

SEE WHAT CUSTOM APPAREL LOOKS LIKE

GEAR UP

MORE FROM THE BLOG

The Perfect Balance: Crafting a Comprehensive Triathlon Training Plan

The Power of Custom Athletic Apparel: Boost Your Performance and Confidence

Triathlon Training 101: Proven Strategies for Avoiding Injuries